The Year of the Hare is one of the few Finnish literary works known in other countries, where it is often marketed as a picaresque novel with environmental themes. It was originally published in 1975 and is now available in translation in 18 languages. According to the edition I read, the book is a best-seller in France, where it has “acquired a higher intellectual status” than in Finland.

This is the story of Vatanen, an unhappy journalist who hits a hare whilst driving with a colleague in the countryside. He leaves the car and runs into the forest in search of the injured hare. Suddenly he loses all interest of going back to the city. He does not go back to the car and his colleague drives off. Some days later he calls his wife saying he is not coming back (“cry quicker, or the call will get expensive”) and starts a journey through Finland with the hare, taking up a series of jobs and having many adventures on the way.

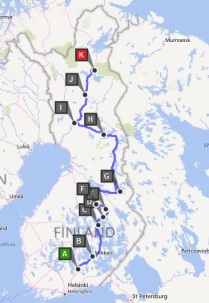

Approximate route of Vatanen’s trip. Bing Maps

His actions are never explained. It is hinted that the decision to drop out was due to his dissatisfaction with consumerism. He recalls how difficult it was to move around inside his flat which was full of “clumsy modularized furniture”. He was also unhappy with his role in the production system, which he consider to be no more than processing information into a digestible form for the masses, something very different from his dream of interviewing “some misrepresented person, ideally someone oppressed by the state”. The journey allows him to achieve freedom.

As he travels, he starts to notice and appreciate the natural environment, in contrast with his attitude while driving with his colleague, when the landscape was slipping past their eyes unnoticed. As he ventures deeper into the wilderness, he also starts to value the peaceful and quiet surroundings. The disruption caused by humans to this peace and quiet is evident in a scene where a bulldozer comes rumbling at a lakeside camp, frightening children and cows. However, in this book the wilderness also seems to be a man’s world, which women occupy only to add to the scenery (“Irja look marvellous, sinking into the cool forest mere with her sumptuous breasts”).

Religion does not seem to have an important place in Vatanen’s new life. He takes a nap in a village church while the hare sniffs the flower arrangements and drops “a few innocent pills in front of the altar”. But then he meets a man who couldn’t find hope in Lutheranism, Russian literature, Buddhism, or Anarchism and finally found it in ancient Finland culture, which he considers the true religion of “a true Finn” (decades before this expression was appropriated by Finland’s racist- homophobic party). For that man, it is impossible to practice religion in the cities, because its rites have to be celebrated in the wild. This rites seems to involve the sacrifice of animals like the hare, which he proceeds to kidnap.

The book raises several issues about the relationships between humans and animals. Is it domestication the best way to care for animals? Vatanen receives a permit to retain the hare from the Game Preservation Office on the grounds that he took charge of it when injured, but police wants to confiscate it and let it out in the forest. The hare recovers 300km into the trip but Vatanen then treats it as a travelling companion.

As the book progresses, Vatanen becomes more aware of the ugliness of other people’s behaviour towards animals. This happens for example when he comes across a group of foreign military attachés walking in the woods searching for a bear: “What we want is, first, to get a good look at it, photograph it, you know, and film it. Then shoot it.” Vatanen feels ashamed to join this group, as he recognises that he had never hunted purely for pleasure. He also feels depressed when, back in the city, he sees an old Santa Claus giving a “nasty kick on the hoofs of a tired reindeer and the reindeer surrounded by squalling children trying to get on its back”, and he confronts a scientist who performs vivisection. (“That’s science. Nor is it your concern. It’s my profession”).

The contradiction of treating some animals as pets and others as food is always latent. In a group, Vatanen is asked if he intends to eat the hare when it is fully grown. He says he has no such intention and others agree that no one would kill his own pet. But at the same time, he also devours big portions of beef and pork, because in Helsinki he “usually had difficulty in coping with breakfast, but now the food tasted marvellous”. Later on, it is revealed that the main dish in a party organised by Vatanen is hare, which creates an awkward situation.

The book also deals with people’s attitudes towards the environmental concerns of others. Vatanen’s actions are often met with incomprehension. A girl asks him if he’s not a criminal because he is coming out of the forest. Later on he knocks at a house and the owners call the police and he is arrested for vagrancy because he is wandering aimlessly, so he might be a danger to the community (“he hasn’t even got a car”). Ironically, the National Institute of Veterinary Science in Helsinki is the only place where he isn’t stared at for carrying a wild animal.

Life in the wilderness is not easy and loving animals can be a heavy load. He maintains that anyone can live that life provided they had the nous to give up city life and trust on their instinct of self-preservation. But other scenes also show his vulnerability in the natural world. In fact, he is only able to lead a life on the road because he relies on the generosity of strangers. For example, on a snap decision he jumps out of a bus just before it starts to rain and then has to beg locals to put him up for the night.

Vatanen often acts on instinct, which is probably a way for the author to remind us that humans are also part of nature. He also behaves irrationally in many occasions. He befriends a moonshiner and the more he drinks the less interest he feels in the forest fire that surrounds them. His love for animals also seems to apply only to cute leverets and calves, not to adult animals. He sets a trap for a raven and recognises that “there was enough cruelty in him to laugh out loud at his foul play”. He also goes on after a bear for several hundreds of km in Soviet Russia just to kill him. In the end, he is charged with several crimes, including cruelty to animals, hunting protected animals, and retaining a protected wild animal.

The book is an easy read, as it is made up of 24 short and entertaining chapters. The author does not push his message too hard. However, the flow of the narrative is disrupted by a huge gap in chapters 19-20, where unexpectedly Vatanen wakes up 170km from the last scene and with no recollection of how it ended up there.

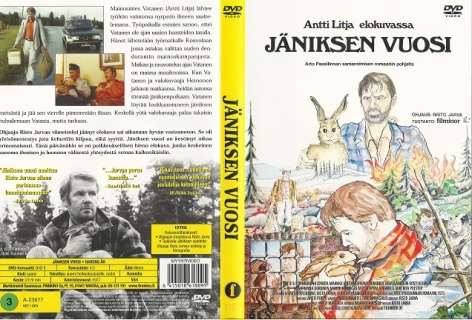

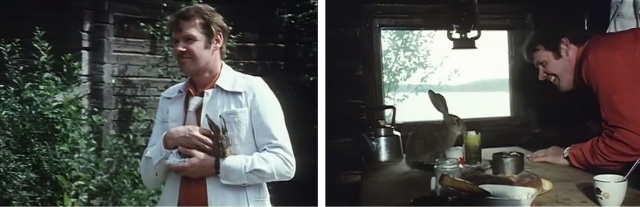

The Year of the Hare was adapted to film in 1977 by Finnish director Risto Jarva. Unlike the book, the film shows Vatanen’s pre-hare life in Helsinki, and how he wants to abandon his “classy, trend-maker, confident, active, highly streamlined” persona. He also has more explicit concerns about issues like greenhouse gas emissions and nuclear waste. His evil side is not shown and the contradictions in his behaviour are less obvious, although he seems to have a tendency to express that he rejects material things by throwing them into the wild, including his necktie, a deodorant can, and a radio. There are nice shots of the Finnish wilderness but also hilarious scenes, when a tour guide asks him to act the Finish man from the wilderness to please foreign tourists.

For some reason, thirty years later, somebody thought it was a good idea to make another film version of the book, called “Le Lièvre de Vatanen”, a French, Belgian, and Bulgarian co-production filmed in Canada. Here, Vatanen is not wandering but goes to places where he knows family and friends. On the way he gets involved with a woman (just an excuse to show breasts on film) and has many adventures when he is invariably saved by the hare. A mess.

The Year of the Hare is an interesting story of human beings trying to relate with the natural world, in the vein of Aleksis Kivi’s Seven Brothers, another Finnish classic. The question raised by the book about the challenges of considering animals as friends and not as food are also explored in “Lamb“, a recent film focusing on a very different setting, that of contemporary rural Ethiopia.

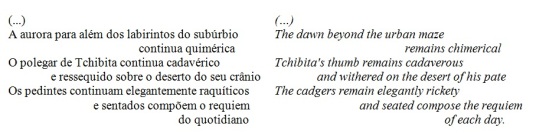

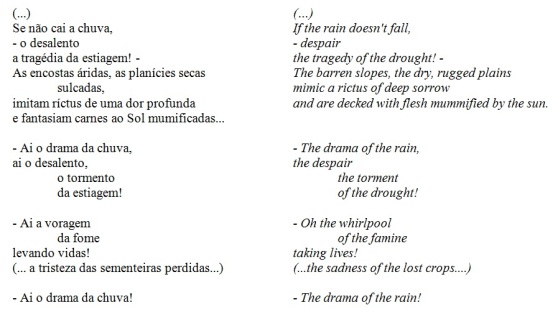

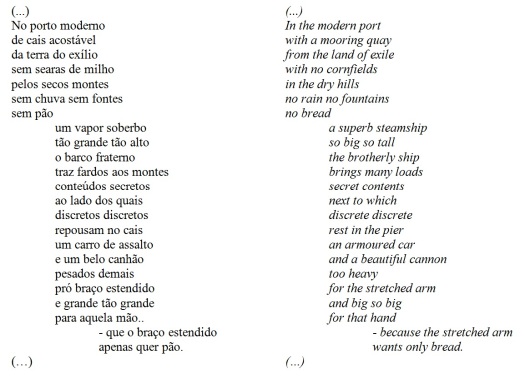

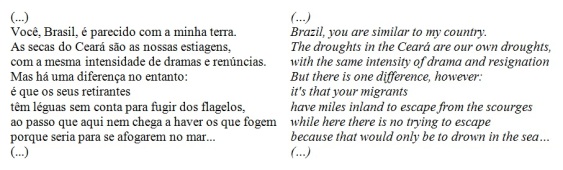

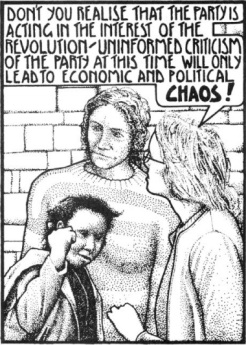

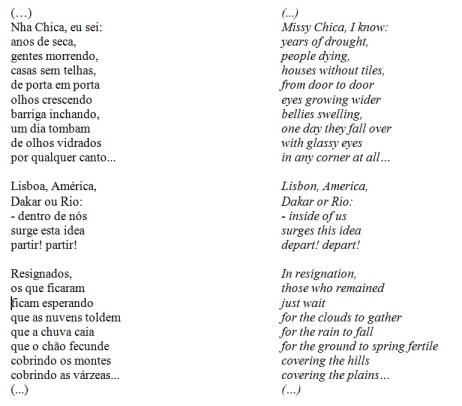

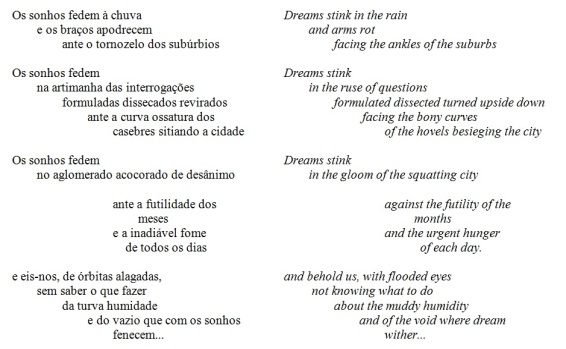

excerpt from José Luiz Hopffer Almada-Meio-dia putrefacto[Rotten midday] (1986).

excerpt from José Luiz Hopffer Almada-Meio-dia putrefacto[Rotten midday] (1986).